Jetpacks, robot girls and flying cars were the promises for the 21st century. Instead, what we got are self-contained mechanized vacuum cleaners. Now a team of Penn State researchers are studying the requirements for electric vertical take-off and landing vehicles (eVTOL) and also developing and testing the potential sources of battery power. “I believe that flying cars have the potential to save a lot of time, increase productivity and can open up the corridors of heaven for transportation," said Chao-Yang Wang, holder of William E. Diefender Chair of Mechanical Engineering and director at the Center for Electrochemical Engines, Penn State.

Electric vertical takeoffs and landings vehicles are a very sophisticated technology for batteries for now. The researchers has defined the technical requirements for flying car batteries and report today (June 7th) in Joule about a prototype battery. “High energy density is required, so that it can stay in the air,” says Wang. “And you also need it to be capable of high power for take-off and landing as a lot of force is needed to raise and lower the vehicle vertically”. Wang noted that the batteries also need to be recharged quickly in order to generate high revenue during peak hours. He sees that these vehicles need to take off and land frequently and recharges quickly. “It would require 15 trips, twice a day during peak hours, to justify the cost of the vehicles," Wang said. The first deployment will be likely from a city to an airport that carries three to four people for around 50 miles.

Weight also plays a significant role in these batteries as the vehicle must lift and land those heavy and bulky power sources. Once the eVTOL starts, the average speed would be 100 miles per hour for shorter trips and 200 miles per hour for the longer ones. eVTOL batteries needs to be quickly charged. These batteries could withstand more than 2,000 quick charge cycles during their lifespan. In order to achieve this, the team took advantage of the technology it was working on for the batteries of electric vehicles. The key to fast charging is to warm the battery to allow it to charge quickly without the formation of lithium spikes, which can damage the battery and are dangerous to the battery health. But it turns out that heating the battery also drains the energy quite rapidly contained in it.

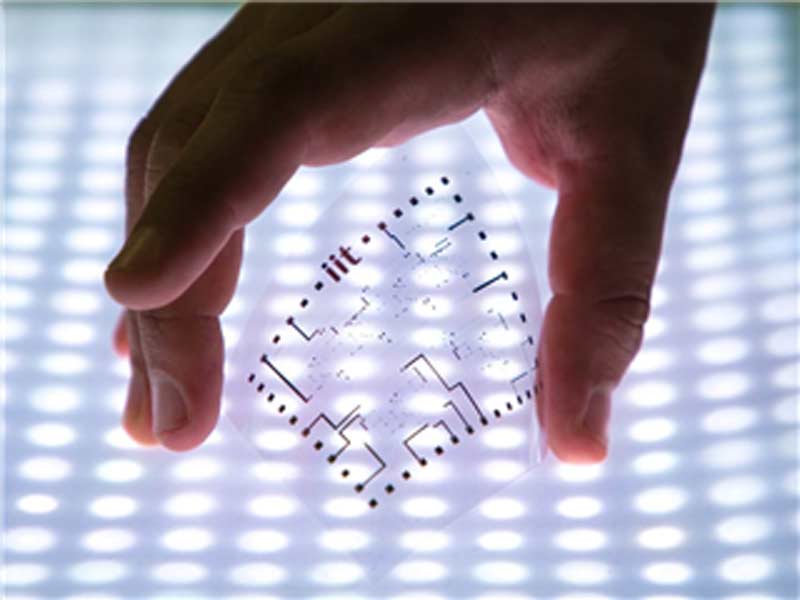

The researchers heat the batteries by incorporating a nickel foil that quickly raises the battery temperature to 140 degrees Fahrenheit. "Under normal circumstances, the three properties required of an eVTOL battery works contrary to each other," said Wang. High energy density reduces fast charging, and fast charging generally reduces the possible charge cycles, but we can now achieve all three into a single battery.